Downward Spiral of Sector Rotation Strategies

What does the research say about sector rotation strategies?

Welcome to +114 new subscribers this month & +307 over the last 90 days.

I started Tuttle Ventures in order to help people find lasting financial security.

If you like what you are reading, consider subscribing today:

Newsletter Rundown:

What is a sector rotation strategy and how does it work?

What does the research say about sector rotation strategies?

The Myth of Sector Rotation Strategies

Hindsight is 20/20

Naïve Long Only

Not every cycle is created equal

Final Word

What is a sector rotation strategy and how does it work?

A sector rotation strategy is an investing approach that focuses on allocating capital across different sectors of the market. This type of strategy seeks to capitalize on the cyclical nature of sector performance by rotating capital between sectors in order to take advantage of changing market conditions.

In general, sector rotation strategies involve identifying which sectors are performing well and then reallocating resources into those areas while simultaneously reducing exposure to underperforming sectors.

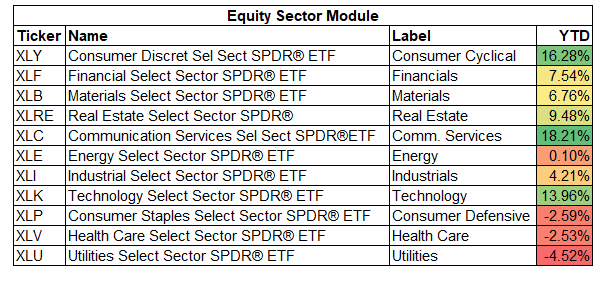

Conveniently, SPDR Sector ETFs offer a full product lineup to support a sector rotation strategy:

The idea is that an investor can benefit from higher returns in those over-performing sectors while also limiting losses if a particular sector begins to decline.

In practice, tracking these 11 ETFs across investor portfolios morph into a tangled web of dozens of positions. Under close scrutiny, positions often contradict what advisors claim about a business cycle at face value.

In 2017, the popularity of sector rotation strategies blew up in the one-size fits all ETF space.

There are now 19 different ETFs that attempt to mimic this investment approach.

With a six year track record it is still considered an early investment fad.

What does the research say about sector rotation strategies?

“The Myth of Sector Rotation Strategies” published back in 2008 by Molchanov & Stangl, provides an overview of sector rotation strategies.

This paper uncovers the underlying reasons why sector rotation strategies tend to struggle, presenting three unique findings that shed light on this perplexing dilemma.

The analysis investigated industry performance over 10 National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) dated business cycles from 1948 to 2018.

The study found: “The significance levels observed are only marginally different from those expected to occur randomly, without any systematic outperformance…With transaction costs, sector rotation performance quickly dissipates.”

Let’s take a closer look…

#1 Hindsight is 20/20

The key problem with sector rotation strategies is defining where we currently are in a business cycle and for how long. Typically investors don’t try to claim with any level of certainty a defined business cycle because individual companies have other fundamental components that are meaningful in the long run.

Last month, I asked Twitter where we are in the business cycle, not surprised there was not majority consensus:

Ok, let’s just assume you can get a business cycle perfectly timed right… how long until you have to trade again?

Business cycles are constantly in motion (hence the term “cycle”) and even with perfect timing you don’t have a clear definition until lagging economic indicators many months later come in to justify a period in time for rebalancing.

There is often a lag between economic events – such as an interest rate hike or cut – and the real economy. This can be especially true with monetary policy decisions; investors may think that they are making rational decisions based on current information, but in reality, these decisions may be too late to capitalize on short-term market movements because of the lag in economic data.

Rebalance too late, and you miss a sector rotation entirely, rotate too early and you may sell before a sector even comes into favor.

Even a broken clock is right at least two times during a day.

It’s my opinion that leading economic indicators are much more helpful because markets are usually forward looking, and clearly defining a cycle is less important for individual companies.

Look at the correlation of a broad sector rotation strategy ETF XLSR 0.00%↑ compared to SPY 0.00%↑ (0.978) is there really any meaningful statistical difference for an active manager?

As Bodie, Kane and Marcus (2009) put it: “sector rotation, like any other form of market timing, will be successful only if one anticipates the next stage of the business cycle better than other investors.”

Going back to the original paper, The Myth of Sector Rotation Strategies, the results suggest that no variation of sector rotation provides systematic outperformance, questioning the popular belief that timing sector investments with business cycles generate excess returns.

Naïve long-only

I’ll admit, there is no shortage of quantitative research in the market to support any pre-existing narrative.

But sometimes an application of common sense is in order.

Think about it, in order to capture the full potential returns of a sector rotation strategy— you need to be able to go long and short the winning and losing sectors.

A recent example of this is last year, when energy was the only positive sector.

Going only long any other sector would have negatively contributed to absolute returns, (if you only stick to the SPDR basket of ETFs)…

If you are only long sectors during an economic slowdown it is like “walking uphill, both ways, in the snow”.

Not every cycle is created equal

Another step in forecasting the performance of a sector rotation strategy is to assess the status of the economy as a whole.

The problem is every business cycle can be dominated by different sector weights, creating outsized effects in one cycle that may not translate to another.

This makes the contribution of historical sector allocations will never have the same marginal contribution to portfolio returns.

The size of pie slices is constantly changing.

For example, look at the change in sector weights for the S&P 500 Index from 2002 compared to 2023.

Going long industrials back in 2002 is starkly different from going long industrials in 2023.

The obvious shift in technology, financials and consumer defensive distorts the starting level of when a sector rotation strategy is put in place.

When energy makes up only 5% of the the S&P 500 index, what level of confidence do you need in the business cycle to allocate 50%+ to the energy subsector?

Dismissing technology at a minimum means an active share of 23 in today’s market.

In a paper published by Newfound Research “Using PMI to Trade Cyclicals vs Defensives” the study used data from the Kenneth French website, and extended a sector rotation study back to 1948, and similarly found that changes in PMI (regardless of lookback period) are not an effective signal for trading Cyclical versus Defensive sectors.

The study concluded, “We find little evidence supporting the notion that PMI changes can be used for constructing a long/short cyclicals versus defensives trade.”

Sector strategies tend to underperform because they lack diversification and miss out on potential returns associated with shifts in sectors or industries between rebalancing periods.

Newfound comes back to suggest: “A more reasonable expectation might be that Cyclicals tend to outperform Defensives during an expansion, and Defensives tend to outperform Cyclicals in a contraction, but there may be meaningful exceptions depending upon the particular cycle.

Final Word

There is no one-size-fits all approach when it comes to investing; instead investors must carefully evaluate each situation independently before making decisions about whether or not a particular sector rotation strategy makes sense for them. By understanding the nuances, smart investors can evaluate the merits of an active investment strategy.

As most of our readers are aware, we favor bottom up fundamental analysis (i.e., company fundamentals) as well as top down macroeconomic factors in a tandem to create an investment portfolio.

With this combined knowledge in hand— alongside sound investment practices—are essential for any long term investor.

Thank you for reading and I am grateful and humbled to be able to learn, grow and invest alongside you at Tuttle Ventures.

Vision, Courage and Patience leads to successful investing.

Best,

Darin Tuttle, CFA

This is not investment advice. Do your own due diligence. I make no representation, warranty or undertaking, express or implied, as to the accuracy, reliability, completeness, or reasonableness of the information contained in this report. Any assumptions, opinions and estimates expressed in this report constitute my judgment as of the date thereof and is subject to change without notice. Any projections contained in the report are based on a number of assumptions as to market conditions. There is no guarantee that projected outcomes will be achieved.

Neither the publisher nor any of its affiliates accepts any liability whatsoever for any direct or consequential loss howsoever arising, directly or indirectly, from any use of the information contained herein.

Unless there is a signed Investment Management or Financial Planning Agreement by both parties, Tuttle Ventures is not acting as your financial advisor or in any fiduciary capacity.

When you say business cycle, are we talking ABCT?

I mostly agree with this, but I tend to think it would be better to look at equal weighting each sector with a slight tilt towards 2 sectors you think would do well each year. Additionally, you can use some quantitative metrics (fundamental and technical) to drive which sector you allocate slightly more to. You marry this with determining where consensus in general is for the business cycle. Using this as a guide for what not to buy, rather than to buy, yes this will lead to you potentially being early, but willing to stay overweight slightly to those sectors you think will do best in the next phase of the business cycle I think could result in more frequent success.

I actually did a Sector Equal Weight portfolio back-test with a quarterly rebalance and it crushed the S&P500 over nearly every horizon I could measure in Ycharts. This portfolio would rebalance quarterly to maintain an equal percentage across each sector SPDR ETF. Important to note: I excluded XLC and XLRE due to their recent inception date so i could get more historical data. Now what I will say the major drawback in this is the fact that many of the SPDR Sector ETF's often have over 40% of their portfolios invested in two - four companies. XLY is like 43% TSLA and AMZN. FWIW, I validated this by Equal Weighting Invesco's EW sector ETF's and yes got much better diversification, but much worse long term performance and annual standard deviation.... The other wrinkle here is the creation of new sectors or the movement/recategorization of some individual stocks, some of them massive, into other sectors. Once again, why I believe its imperative to have a little each year in every sector.

Would love to have a conversation about this in more detail if you are open to it. I still standby the fact that there are thoughtful ways to do this and one of them is making sure you have at least some money in every sector each year as to not create a situation where you are precisely wrong.